Many of you have asked us in recent months what is going on in Bolivia, our home for the last seven years. Rather than send half-baked replies to each and all we thought that we would sit down and make an effort tell you everything we know all at once. Don’t worry. It won’t take that long. -- David and Kelly Clark Boldt

RALLY FOR "EL SÍ" -- May Day rally closed the campaign for "Yes" on autonomy. Photo from El Deber

THINGS ARE ON A COLLISION COURSE here at present.

On May 4 the state (called department here) of Santa Cruz will vote on whether or not it wants “autonomy.” The resolution seems almost certain to pass, and within a few weeks after that, several other departments in eastern and southern Bolivia will vote on similar resolutions.

The national government of Bolivia under Evo Morales, the Marxist indigenous president (and friend of Venezuela president Hugo Chavez). has said these resolutions are illegal, and has vowed to prevent any effort that would subvert the authority of the national government. Morales was swept into office by the largest margin in Bolivian history two years ago.

Yet at the same time Bolivia has a long tradition of going right up to the point of crisis, then backing off. Moreover, there does not appear to be at present an issue that would trigger the outbreak of some sort of civil war.

One is tempted – especially if one is an optimist – to classify the current situation as “hopeless – but not serious.” But if one is pessimistic, there are also reasons to believe that the current situation might be more explosive than any the nation has faced in the past.

Our own forecast is that the voting will be accomplished without much fuss, and that the test of strength, if it comes, will occur further down the road.

“Autonomia: What will it mean?

One reason for this is that the exact meaning of “autonomia” has been kept, either brilliantly or deceptively (depending on one’s point of view), vague. No one seems to know what, exactly, it will mean.

I was talking about what the future might hold with the head of a big, important company in Santa Cruz the other day while we were both watching a high school basketball game. Did the civic authorities who were backing autonomy have a plan for what they would do once the referendum passed,? I asked. “Not that they’ve been willing to share with me,” he replied.

Apparently there will be elections for a governor (although we already have an elected “prefect” for the department) and assembly, and the department will take charge of schools, public health facilities, and the like. The department will have its own police force. There is some talk about new local taxes. (Almost all local government revenue now comes through the central government.) And the autonomous status could interfere with thenational government's efforts to confiscate underused land from large landowners and redistribute it.

But no line has been drawn in the sand, and presumably there is still room for negotiation and compromise, when it comes to the really crucial questions like the forwarding of tax revenues to the central government, the controlling of natural gas and petroleum fields in the department, or the enforcing of exportation policies

Why, you might ask, do people in Santa Cruz want autonomy? The reasons run deep and have roots that reach back way before Evo Morales took office. Indeed, causes for the sectional rivalry go all the way back to the beginnings of Bolivian history.

Independence was thrust upon Bolivia

Bolivia is really an accident of history. Bolivians did not win independence. It was thrust upon them. During most of the time that Simon Bolivar and José de San Martin and others were fighting the famous battles against those who wished to remain loyal to Spain, the area that is now Bolivia was controlled by a loyalist regime that was, however, independent of the main loyalist groups in Peru and elsewhere. When the loyalist forces elsewhere were defeated, the loyalist regime in Bolivia broke into factions that fought among themselves, and it disappeared.

When Bolivar’s principal general, José Antonio de Sucre, came into the region at the head of an army, he was entering a political vacuum. He asked a group of locals who had convened as sort of a de facto ruling body what they wanted to be – an independent country, part of another country, or whatever. They opted to become a separate country.

Sucre, knowing that Bolivar might not like this because it conflicted with his dream of a United Latin America, suggested that they name the country after Bolivar to win him over, which they did. Bolivar at this point had also come to feel that if Latin America was not going to be united immediately, there probably should be a buffer state between Argentina, which had been ardent for independence, and Peru, which had been a hotbed of loyalist sentiment. Bolivia filled that need.

Bolivar agreed to be the first president of Bolivia, and actually made a sort of triumphant tour through the country before handing over the presidency to Sucre, who served until he was nearly assassinated, at which point he quit.

But there were few formative shared experiences for Bolivians that would serve to weld Bolivians together. Big chunks of what was originally Bolivian territory were bitten off by Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Paraguay in the years following independence without much protest from the people who were annexed into the other countries.

Two regions with little in common

What was left were two big regions that had little or nothing in common geographically or historically, except for a period when they were loosely administered together by Spanish colonial authorities as Alta Peru (Upper Peru). On the western side of the country was the “Altiplano,” or High Plain, an arid, windswept area located between two ridges of the Andes Mountains. La Paz, located in a depression on the Altiplano, was originally a place where mule trains taking silver from the mountains of Bolivia to the ports of Peru could take shelter out of the wind and get some water.

On the eastern side of the country were the lowlands – broad, fertile, well watered (indeed often overly watered) plains that had once been at the bottom of an inland sea. This is the area where Santa Cruz is located.

The two regions have been quite separate even into antiquity, with different Indian tribes inhabiting each. There is actually an ancient Indian “fort” located in the mountains just west of Santa Cruz that probably served, among other purposes, as a guard post to inhibit lowland Indians from invading the Altiplano.

The pattern of neglect continues

From very early on in Bolivian history efforts were made to develop the eastern lowlands by, for example, allowing trade to flow through the Amazon River by constructing a railroad around a treacherous set of rapids on a major tributary of the Amazon. Such efforts were unfailingly opposed by La Paz and the Altiplano, which feared losing their economic and political dominance of the country.

This pattern of neglect continued in the 20th century. One result was that the railroad system of western Bolivia was never connected to the lines in the east. In fact, to this day there is no transcontinental railroad across the upper part of South America.

A paved road didn’t reach Santa Cruz until the 1950s, at which time it was a sleepy, insular backwater town of around 50,000 people. Since then it has exploded to a city of over 1.5 million, passing La Paz to become Bolivia’s largest city in the census of 2001.

Cruceños are quick to point out that they had to pull themselves up by the bootstraps with little help from the national government. They are proud of the fact that they developed their own infrastructure such as their large electric cooperative, sewer and sanitation systems and telephone companies. They are now incensed when they hear the Morales government talk of plans to nationalize these same organizations.

They can also quickly catalogue the continuing examples of neglect by the central government. The post office in Santa Cruz – and there is only one – is housed in a disheveled, tin-roofed building in downtown Santa Cruz that is filled with puddles when it rains, while the post offices in smaller cities are little granite and ceramic tile palaces. (The post offices are also eerily empty. Mail service in Bolivia is so limited and unreliable that it is little used. Even advertisements are sent by private couriers.)

A boom town on the plains

Santa Cruz today is the center of a thriving agricultural area where soybeans, sugar, rice, sunflower seeds, and other cash crops are grown on large farms. Every other business seems to be either a tractor dealership or a seed store. It is something of a boom town, buoyed by rising commodity prices and fueled by an influx of businesses and people leaving other cities in Bolivia. New apartment buildings, houses and offices are going up everywhere, with plenty of help wanted signs around, even in car washes. Sales of commercial property have been brisk over the last several years.

The downside is that the place has a sort of half-finished feel to it. It looks like what it is: A city that has been thrown together over the last 50 years, with lots of dusty unpaved back streets, sidewalk-less thoroughfares, and a glut of vehicles far greater than its streets can handle. The city has recently started making some nice little parks, but until then there was no attractive common space other than a nice central plaza.

When the wind isn’t blowing, parts of the poorly sewered city even smell bad, though boosterish locals might claim that it is the smell of success. Cruceños like to claim that Bolivia’s recent annual growth rate of close to 5 percent has been achieved by Santa Cruz growing 10 percent a year while the rest of the country’s growth stays flat. This assessment ignores the good times currently underway in Bolivia’s mining areas, but otherwise it’s probably not that far off the mark.

An almost Texan fear of government control

The advent of Evo Morales has only exacerbated the antique antipathies between the eastern lowlands and the Altiplano. Morales’ so-called 21st century socialism with its emphasis on centralized control and anti-entrepreneurial biases just annoys the hell out of Cruceños, who have an almost Texan belief in the importance of private initiative and the perils of government control.

Morales has never had much support in Santa Cruz. It was considered amazing that he got 30 percent of the vote in Santa Cruz in the election in which he won over 50 percent nationwide. He only got that much because many people thought that Morales, a former mining union organizer and leader of coca growers, would be less of annoyance as head of the government than he had been as head of the opposition. During his rise to power he had specialized in disruptive protests and road blockades.

Others thought he “deserved a chance.” A few thought it would just be fun to see him in power. “It will be like watching a monkey play with a pistol,” one friend told me.

Those people are mostly sorry now, and the president’s support in this part of the country has, according to polls, dwindled to considerably less than 30 percent. Could it have been different? Maybe.

It would have required something on the order of a second coming of Franklin Roosevelt, and would be a lot to expect of an ex-union leader with no executive experience. Still, Morales got off to an interesting start with his “nationalization” of Bolivia’s petroleum industry two years ago, which showed a canny blending of leftist theatricality with centrist pragmatism.

A successful “forced renegotiation”

It wasn’t really a nationalization, however. (If it had been it would have been Bolivia’s third nationalization of the oil business, thereby setting a world record.) What happened can be more accurately described as a “forced renegotiation.”

It started off radically enough with a May Day takeover of petroleum companies in which troops occupied the oil company facilities and frisked the employees as they left work each day to make sure they were not trying to sneak out with any computer CDs. (The troops, however, had not been briefed on flash disks, and let those pass.)

However, none of the dozen or so oil companies has actually left the country, and the deals that were finally struck have left the oil company executives grinning like Cheshire cats ever since. One company president told his employees at the annual picnic that the new contracts were the best thing that could have happened to the company, taking all the risk out of the oil business. The new government oil company, he said, was now required by law to buy whatever gas or oil their company could pump out of the ground at a satisfactory price.

The main defect that has surfaced regarding the new contracts is that they eliminated the incentives to find more oil and gas, replacing them with pledges by the companies to spend money on exploration. The result, as any student who passed Economics 1 could have told the government, is that the companies have spent the money (to the extent they have spent it) on sure-fire exploration of known fields, rather than higher-risk searches for new reserves.

A gas shortage emerges

The result is that Bolivia does not have enough gas at present to meet its contractual obligations to ship gas by pipelines to Brazil and Argentina, and is going to have to pay Brazil a cash penalty. Bolivia is also forced to become increasing dependent on imports for diesel fuel, which is increasingly in short supply. Trucks wait in mile-long lines for their share of diesel when supplies dwindle, and the most recent shortage continued for months.

Another defect is that one company did not agree to continue even with its previous level of exploration. That was Petrobras, the half-government-owned Brazilian petroleum company, which had been the major investor in Bolivia’s petroleum resources. Since the new agreements were hammered out Brazilian President Lula da Silva, who has tried to be sympathetic to Morales, has said that the company was going to resume exploration, but there is no sign yet that it is doing so.

However, and more importantly, the finesse that the Morales government showed in the oil negotiations has not reappeared, and the remarkably broad coalition that brought Morales to power has largely disintegrated as the situation in the country has become increasingly polarized. The Morales government has lost the support of entire provinces through the mismanagement of a sequence of crises.

Losing battles in Cochabamba, Chuquisaca

At the end of his first year in power Morales’ movement attempted to oust the governor of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes, a former presidential candidate who had become increasingly oppositional to the government. The pro-Morales and pro-Reyes forces actually got into a mass street fight in the city of Cochabamba, and Morales’ forces lost, leaving Reyes more securely in power, and enabling him to become one of the persons around whom the heretofore somewhat formless opposition to Morales is coalescing.

More recently the Morales government managed to estrange itself from yet another department as a result of a huge, and largely unnecessary, fight within the Constitutional Assembly over the location of the national capital. Bolivia at present technically has two national capitals. The judiciary has its head in Sucre, the original capital of the nation, which is also the capital of the state of Chuquisaca, and, not incidentally, the city where the Constitutional Assembly was meeting. It is located in a valley between the Altiplano and the lowlands, and, like Cochabamba, had supported Morales in his run for the presidency. The executive and legislative branches of the government are in La Paz, where they were moved after a minor civil war around 1900.

To make quite a long story short, the delegates from Sucre wanted the capital moved back to their city, and tried to put a provision to that effect into the Constitution, against the wishes of the Morales government, not to mention the populace of La Paz. The delegates from Santa Cruz and the other lowland departments, eager to diminish La Paz and sow discord into the ranks of the opposition, happily embraced the idea of making Sucre the full-fledged capital again. The argument proved unamenable to compromise and took on a life of its own, becoming a surrogate for other complaints about the Morales government as well.

Finishing the Constitution -- under guard

Ultimately there was mob violence in the streets of Sucre, and the Constitutional Assembly, by then attended only by its pro-Morales members, was moved to the Altiplano city of Oruro where the process was completed, under dubious legality and military guard. Meanwhile the prefect of Chuquisaca, who had been elected as a member of Morales’ MAS (Movement to Socialism) party, broke with the government, resigned and is now living outside the country in self-imposed exile. (At one point, the new constitution was supposed to be put up for voter approval the same day as the autonomia referendum, but was pulled back, probably because of uncertainty as to whether it would pass.)

When Morales and his party came to power he had had the support of five of the nine departments, including Cochabamba and Chuquisaca. Now he probably no longer has the firm support of the latter two, giving him solid support in only three of the nine departments.

Who are the "oligarchs"?

The rhetoric between the two sides has heated up. Morales no longer seems to seek any sort of accord with the civic leaders in Santa Cruz, whom he refers to only as the “oligarchs.” This terminology is meant to classify them as oppressors of the working class in Marxist analysis. However, the business leaders of Santa Cruz have kind of cottoned to the term. The society section of the main newspaper in Bolivia recently carried an account of a group calling themselves the “Vacationing Oligarchs,” who had just completed a sojourn to the beaches of Brazil. The other day we spotted a bumper sticker on an oversize SUV reading, “100% Oligarch.” And a strapping new horse in the equestrian competitions at Santa Cruz’ Club Hipico – a known hangout for the city’s upper crust – is named “Oligarco.”

Who, exactly, are these “oligarchs.” We have seen the “oligarchs” described in an Associated Press story as “white descendants of the Spanish settlers.” But this is misleading. There are a few descendants of the “original Spanish settlers” still around. (We personally know one, a hotel owner.) But there aren’t many, as one can deduce from the aforementioned fact that before 1950 there were not many people here at all.

(In other newspaper stories Santa Cruz is referred to as the “rich renegade” state and other press coverage would leave readers outside of the country to believe that Santa Cruz is chock full of millionaires. Believe us, in seven years we sure haven’t seen many that would met that criterion. Obviously the international press has not done much of its own investigation.)

Most of the “oligarchs” are in fact descendants of people who immigrated to Santa Cruz in the last 50 to 100 years, from places other than Spain. Perhaps the prime example is the current head of the Committee for Santa Cruz, who has the very un-Spanish name of Branko Marinkovic, and whose parents came to Bolivia from the former Yugoslavia.

A polyglot upper class

I run a website that covers the sports events of four elite prep schools in Santa Cruz, and a perusal of the team rosters gives an interesting insight into the polyglot nature of the city’s upper class. There are more Yugoslavs (Matkovic, Ibrahimpasic), Arabs (Rik, Abuawad, Dajbur, Mustafa), Iranians (Nowrooziyani, Hajari, Shoaie), Italians (Foianini, Gamboa, Gioto, Cocciani), Germans (Grote, Linggi), and lots of Asians (Yuan, Zhau Fua, Sakuma, Shin, Oh, Kook, Li, Song, Yong, and so on). Few are more than second generation immigrants. Many are freshly arrived.

Whoever the “oligarchs” are, it’s important to keep in mind that the autonomia movement is a mass movement. Polls indicate – and it will be interesting to see what the final count is – that the “si” vote in the autonomy referendum will exceed 70 per cent. Huge rallies have been held in support of autonomy, with far more people present than just oligarchs.

A Million Cruceño March

The largest, a town meeting (or “cabildo”) convened at the foot of the huge statue of Christ in the middle of the city a year ago, was said by the newspapers to have attracted 800,000 people. David was there, and thinks there were at least 500,000. He has covered the big marches convened on the mall in Washington (Million Man March, Promise Keepers, etc), and the gathering here was of that magnitude. Vast crowds of people stretching in all directions. And all kinds of people – taxi drivers, beauticians, maids, construction workers – from all manner of ethnic backgrounds including, most definitely, many people of indigenous heritage. The latter were also represented on the speakers platform.

In much of the American and European press, the struggle in Bolivia is depicted as one between the good and wholesome indigenous people lined up behind their fearless leader, Evo Morales, and the “white” forces of evil and oppression. As the daughter of friends of ours very innocently said after spending a year as an exchange student in Germany, “Indians seem to be in fashion.”

Morales shaped by his personal history

But the situation here defies simplification. Evo Morales is widely acclaimed as the first Indian head of state in Latin America since Mexico’s iconic leader Benito Juarez. However, according to people who grew up with him he reportedly can't converse in any Indian language. His Indian heritage seems to be, in part, a fashion statement, expressed in his hand-tooled leather jackets, made by a well known Bolivian clothes designer, and distinctive broad-stripe sweaters.

More than any ethnic identity, his strongest allegiance seems to be with the coca growers who were his political base. (Most are former tin miners, displaced when world demand for tin declined, and the tin produced by Bolivia’s government-run monopoly became the most expensive, and lowest quality, on the world market.)

His early years of poverty left him with a strong resentment of people with perceived power or money which, unfortunately, prevents him from being a president of all Bolivians. He specializes in polarization and pitting one faction against another because that is how he views the world. It served him well when he was leader of the opposition and successfully overthrew two elected governments, but it’s doubtful that augmenting cultural and regional polarization will lead the indigenous population or other tragically poor Bolivians into prosperity.

To the extent that the Morales has acted as an advocate for indigenous people it has been an uneven effort in which it has become increasingly clear that some Indians are more equal than others. The Indians of the lowlands – Guaranis, Chiquitos, Ayeoros, and so on – perpetually get the short end of the stick, just like their paler fellow lowlanders.

The central government has, in a number of celebrated cases, sent educational materials in Aymara or Quechua, the principal Indian languages of the Altiplano, to lowland communities where no one, whether of Indian descent or not, spoke or read those languages.

An indication that ethnicity plays less of a role in Santa Cruz than elsewhere in Bolivia came in the 2001 census in which Bolivians were given nine choices to describe their ethnicity, which might have seemed to cover most of the available possibilities. However, over half of the residents of Santa Cruz checked “none of the above.”

Battles over exports

The biggest rupture between Santa Cruz and the Morales government has taken place in recent months over the issue of agricultural exports, which are a major part of the Santa Cruz economy, and not so important in the Altiplano, which is above the tree line and hasn’t been profitably farmed since Incan times.

Ostensibly to cut down on the rising inflation that has been taking place in Bolivia by increasing the supply of agricultural products, the Morales government, by decree, banned the exportation of beef, chicken, and, most importantly, vegetable oil. This last hit Santa Cruz soy and sunflower seed farmers right where it hurt.

The high international prices for these products should have made it possible for Bolivian producers to earn greater profits, to expand acreage and employment, and to boost the national economy. The export bans seem to be a classic case of the government shooting itself in the foot, economically speaking, especially since prices of agricultural products in Bolivia remain relatively low and supplies plentiful.

Counting too many chickens

One aspect of the affair definitely illustrated the central government’s lack of sophistication and knowledge in economic affairs – the ban on chicken exportation. The ban on beef exports was never very important because Bolivia doesn’t export much beef. In fact it imports a lot of beef from neighboring Argentina, one of the world’s major beef exporters. The most expensive item on the menus of Bolivian restaurants is usually an Argentine steak.

Chicken was a somewhat different matter. The government apparently really thought that Bolivia exported a lot of chicken. However, it turns out that chicken happens to be one of the most heavily regulated exports in the world because of the danger of spoilage, avian flu, and so forth. Only one company in Bolivia had successfully met the international sanitary standards, and it was exporting only a small number of frozen chickens to Peru. Moreover, that company and the government had – at least until the exportation ban was announced – been working together to try to open the Japanese market to Bolivian frozen poultry, which had been considered a worthwhile goal.

To the national government’s credit, once these facts were diplomatically brought to its attention, it dropped the ban on chicken exportation.

The ban on vegetable oil exports has led to more a fractious and involuted contretemps. The vegetable oil producers and their employees, of whom there are many, responded like gored bulls to the government action, with large protest meetings and truck cavalcades. The long-distance truckers went on strike for a period of time to protest the export ban, though they backed down when their pickets and blockades were threatened with violence by MAS-led mobs.

"To arms brave Cruceños"

Ultimately an arrangement seems to have been worked out in which the vegetable oil producers will export their product at international prices, while selling to the domestic market at another, lower price. But the affair has caused a vitriol build-up in the Bolivian body politic.

The leadership of Santa Cruz, it needs to be added, has done little to effect a rapprochement with the Morales government over the past two years. Most recently, the export bans were characterized as deliberate attempts on the part of the national government to cripple the Santa Cruz economy (which may indeed have been one of the goals).

In any event, the walls of the city are awash with anti-Morales sentiments, like “To arms brave Cruceños – Time is running out,” “No to Narco-Communism,” and “Dictator Morales.” Perhaps the coldest is, “Evo Morales Dies in Santa Cruz.” Only a few “Evo Delivers” slogans answer back.

Recently signs of support for autonomia have become ubiquitous in the city in such forms as green-and-white Santa Cruz flags flapping from the tailgates of cars, along with street banners and billboards declaring, “SI! A la Autonomia! Let nothing and no one hold us back!” (This is something of an improvement, content-wise,” on the previous pro-autonomia slogan, which was, “Autonomia, Carajo!,” or “Autonomy, Dammit!”)

Television station breaks have been filled with pro-autonomy ads, with some responding ads from the government urging rejection of the referendum, or at least abstention. The news reports are filled with pro and con commentaries, along with stories on the city government’s opening of an Autonomy Park, on the release of a new autonomy song, and on the freewheeling autonomy dance craze that is reportedly sweeping the city. It feels like New Hampshire during presidential primary season.

Where will it all end? No one can say. Those who argue that this too will pass without disastrous consequences point to the fact that Bolivia has never had major civil unrest on the scale that, say, the United States has had. Even the revered Bolivian National Revolution of the 1950s in which the sainted Victor Paz Estenssoro overthrew by force of arms a military regime that had annulled his election to the presidency, was a relatively mild affair in which only a few hundred people were killed, all told. (By contrast, it has been estimated that 5.000 soldiers died in one 20-minute phase of the Battle of Shiloh during the US Civil War.)

Moreover, the confrontations that have taken place so far in Cochabamba and Sucre have also been brief, as these things go, and involved only a few deaths arising from idiosyncratic circumstances. The one near-battle in Santa Cruz ended with no fatalities. It was over so fast that the global media didn’t even have time to take note.

Occupying the airport

It occurred last year when the national government, for reasons that have never been made entirely clear, sent in military police to take over Santa Cruz’ international airport, the most important in Bolivia.

The civic leaders in Santa Cruz, on learning this, rang the bells of the cathedral, the traditional means of sounding the alarm. People poured out to the airport, which was then sealed off. (Arriving passengers were taken out in taxis on a dirt track that passed through an adjoining ranch.) Much tear gas was fired by the police, and as night feel there was a stand-off between the police and the mob.

During the night efforts continued that would have brought thousands of more protestors to the airport in the morning with the apparent goal of overwhelming the military contingent. Happily, in the dark of the pre-dawn the military were airlifted out. A spontaneous party broke out in place of violence as the airport was “liberated.” By noon, airport operations were back to normal, and haven’t been interrupted since.

Adding racism to the mix

It’s hoped that the rapid and relatively non-violent outcome was an accurate precursor of things to come. But those who say things could be worse this time around note that this time large numbers of people on both sides care passionately about the issues involved this time, more so that in the past.

Moreover, the confrontation is tinged with a complex kind of racism. It’s not a simple whites vs. Indians kind of racism. It’s a more complex sort of racism that involves the mutual dislike between Cruceños, whether mainly Indian or mostly white, who call themselves cambas, and the indigenous people of the Altiplano, who are called koyas. The distinctions are difficult to describe, and many koyas coming to the lowlands are said to undergo instantaneous conversion into camba-ness once they cross a certain river. (“As long as they’re good-looking they fit right in,” an American who studied the situation once told us.)

Koyas, who for the most part are hard-working merchants, are flocking to Santa Cruz where they can make a better living and where they run the large mercados (markets) located around the city. Cambas, in the Koya view, are said to be lazy but blessed with more abundant favorable natural resources.

However, as a general rule the two groups know each other when they see each other, sometimes, with the more traditional groups, more by dress than physical appearance. But even in wealthy neighborhoods where to the outsider’s eye the residents all seem to be just Bolivians, the Bolivians themselves are acutely aware of who is originally from La Paz and other Koya locations, and who is a life-long Cruceño.

Subtle though it may be, this racial, or ethnic, distinction has become increasingly virulent, and it adds volatility to the situation. Moreover, many old-time Cruceños remember that in 1959 truckloads of Indians were sent into Santa Cruz to suppress a separatist movement, and in so doing committed a number of hideous and infamous atrocities. Some of those who remember are itching to get even.

Still, there would seem to be plenty of room, given time, for a Bolivian-style accommodation to be worked out. A one-time political mentor of President Morales said in a recent newspaper interview that it was not too late for Morales to co-opt the autonomy movement. Morales’ own constitution calls for giving Indians – some Indians, anyway – more autonomy in zones where they are dominant to follow their communitarian impulses, even condoning so-called “community justice” in which alleged miscreants are beaten to death by mobs. These “lynchings” have in any event seldom, if ever, resulted in prosecutions of the mob leaders.

Autonomy as an "escape valve"

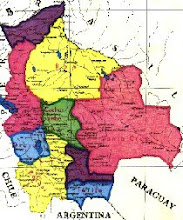

A measure of autonomy for Santa Cruz and the other, smaller departments of the eastern lowlands, sometimes known as the “Media Luna” (Half Moon) because of the shape they form on a map, might provide a handy escape valve for Morales’ experiment in 21st century socialism, something on the order of the boat lifts that removed many disgruntled inhabitants of Fidel Castro´s Cuba. Bolivians in both camps might be reasonably well pleased with a country in which they could take their pick as to whether they wanted to live under the more free market oriented regimes of the autonomous regions, or take part in the more centrally planned socialistic economy of the Altiplano.

The sticky point comes over the fact that Santa Cruz is, in fact, the main engine of economic growth in Bolivia, and, more treacherous still, is the fact that the nation’s petroleum reserves are almost all in the Media Luna. On the other hand, the Altiplano has Bolivia’s still considerable mineral wealth, and maybe, perhaps through the revival of Incan agricultural methods, the Altiplano might be made to bloom again.

As they like to say in television news, only time will tell.

5 comments:

David and Kelly,

This is a great idea. You have done a wonderful job. Thank you so much for taking the time to lay out the recent events and political forces to help the rest of us understand what's going on. An occasional read on the internet of El Deber doesn't do it in such a complex situation. I plan to let the local paper (Salt Lake City Tribune) know about your blog, though they seem to rely on the news services for international news.

I think I have properly subscribed to your blog so it will automatically come to us when you post. Otherwise, I'll check regularly.

Also, loved the pictures. See you soon!

Barbara and Harold

The article was okay, but one part struck me as particularly offensive, and I quote it here:

"Evo Morales is widely acclaimed as the first Indian head of state in Latin America since Mexico’s iconic leader Benito Juarez. However, he doesn’t speak any Indian languages, and doesn’t dwell on Indian lore. The most “Indian” things about him appear to be the hand-tooled leather jackets and sweaters with broad, oddly colored stripes that he fancies. Indeed, for Morales (as for many other Bolivians claiming indigenous status). Indian-ness appears to be in large part a fashion statement."

This is a sweeping statement that may or may not be groundless but certainly is entirely unsupported in this article. How do you know that "Indian-ness" is a fashion statement for President Morales? Do you have unique insight into his mind to know with such detail how he views his own indigenous heritage? Or is this something that you just made up or heard? Please be careful when repeating this type of information that is quite offensive to Bolivians of indigenous heritage. Also, please note the factual error; Evo Morales speaks both Quechua and Aymara, and I have personally witnessed him speaking both languages. Those are, of course, indigenous languages spoken by millions of Bolivians and other residents of the Andean countries.

I lived for two years with the indigenous people of Oruro, and I can assure you that the people there, that live off the land as subsistence farmers and still live and die by the seasons and the quality of the harvest, do not regard their indigenous heritage, nor their traditions and beliefs, as a fashion statement.

You accurately captured that the presidency of Morales has been quite complex, with successes and failures, with good ideas and bad ideas, but please be careful about broad, sweeping statements and assumptions that have no place in this analysis.

David and Kelly,

Thank you so much for sharing this. It is extremely well written and it will help me communicate the situation to others since I'm so frequently asked. I miss you and SC. Hope to hear from you soon.

Love Gesa

David and Kelly,

Thank you so much for sharing this. This will help me communicate the situation to others since I'm so frequently asked. Beautifully written.

I miss you and SC. Hope you're both well and hope to hear again from you soon.

Love Gesa

Thanks for the great history! I have friends in Santa Cruz and other friends moving there so this is very relevant to me. Plus, I just like learning the whys of history and you did a great job explaining!

Post a Comment