New Day Dawning?

Cautious optimism seeps across Bolivia

A remarkable and quite unexpected change has taken place in the political landscape of Bolivia in the last week, resulting mainly from the startlingly moderate version of the proposed new Constitution put forward by the national Congress last Monday. The Congress was threatened by a group of thousands of campesinos marching from various parts of the country to “cerco” or surround the Congress until they passed the constitution and gave Congress a deadline of just a few days to do finish their work. And finish quickly they did.

The result is that there were compromises on both sides, Surprisingly, President Morales gave in on the issue of being able to be reelected two more times and settled with a provision that allowed him one more term, and made a number of other concessions.

A national referendum on the constitution has been set for next Jan. 25, and there are indications that some groups, such as the Comite Pro Tarija, and some political leaders that have been militantly pro-“autonomia” will support its passage.

On the other hand there is a hard-core fringe of leftists and indigenous leaders who accuse President Morales of having sold out. “This is not the Constitution we approved,” said one such leader who had participated in drafting the prior version in Oruro when it was approved under armed guard with only the MAS party constitutional convention delegates present.. He added, “This looks like the Constitution of PODEMOS,” the principal opposition party to the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) Party headed by President Morales.

The new prefect of Oruro, who was recently appointed by President Morales, has said he will oppose the Constitution too.

Opposites oppose newest Constitution.

Opposites oppose

The civic leaders of Santa Cruz who reflect the opposite end of the political spectrum, have called for a national effort to vote NO on the proposed constitution. However, by week’s end the Cruceño leaders were still having a hard time articulating a compelling case against the reviswed version of the constitution.

The Constitution in its new form or its old form is no simple document like the US Constitution. It goes on for scores of pages of fine print Spanish legalese, and the devil or divinity of the document has always been in the details. It may be weeks before constitutional scholars and others are able to comb completely through the thickets of obscure verbiage to find any lurking snakes.

However, a first reading indicates that the major areas of concern have been either removed or rectified to a considerable degree in the more than 100 changes that were made. Private property is specifically guaranteed, as is the right of parents to send their children to private schools. (Both of these had been matters of concern in regard to the previous version.)

The unicameral Congress that many considered way for the MAS party to take total control of the Congress much less just poor political science, has been replaced with a two-chamber legislative branch that will have a single name. The set-asides for various administrative and other bodies guaranteeing that 40 percent of the members be pure-blooded Indians are out.

Crash course for Morales?

Public officials must, however, know at least two languages. This could conceivably pose a problem for many office-seekers including President Morales who reportedly speaks only Spanish, and knows no Indian language. Presumably this can be fixed with a fast immersion course. The exact level of fluency required, in any event, is not specified.

Certain nettlesome questions such as far-reaching land reform are omitted from the Constitution and left for future governments to hash out, though there are limits to how much land one can own.

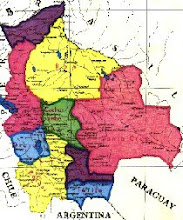

Perhaps most importantly, the newly proposed Constitution recognizes a limited form of autonomia for the departments (states) as well as for indigenous areas, which will have their own elected governors and legislatures with certain designated powers in their regions.

About 30% of autonomia okayed

Juan Carlos Urenda, the architect of autonomia and the man who wrote the “estatutos autonomias” approved by referenda in four of Bolivia’s nine departments, estimates that only 30 percent of the powers allocated to the department in those estatutos are permitted under the new Constitution. Urenda argues that this is not enough, but others, such as the civic leaders of Tarija, who had been in the vanguard of the autonomia movement, think it’s a lot better to have 30 percent than the zero percent permitted under the previous proposal It could be considered as a solid first step in developing a federalist system and they´ll take it, thank you.

In any event many neutral observers had thought that the statutes included some items of dubious wisdom, such as giving autonomous departments the authority to conclude treaties with foreign governments without the approval of the national government.

Moreover, many observers thought that the exact details of the sharing of power between the national and departmental governments did not lend themselves to specific delineation in a constitution, but could only be worked out in a gradual process of negotiation, trial and error, and repeated tests of strength.

The Constitution does provide for centralized authority in the country, and would allow the imposition of socialist schemes to, basically, spread the wealth. So do most other Constitutions, including the US Constitution, if those are the policies advocated by the country’s elected authorities The difference, of course, is that Bolivia’s socialist president is more likely to take that centralized authority, as can be seen in his frequent use of governing by decree and skirting judicial processes for opponents who are in jail without being legally charged.

The threat of re-election

One issue that opponents of the new proposed constitution have latched onto is the provision allowing the president and vice president to be re-elected to a second five year term Morales and Garcia Linera and supporters had wanted that provision to be applied in a way such that it would allow them to have two more five-year terms. In a crucial compromise, this provision will not apply to the first president elected under the new constitution, who everyone presumes will be President Morales. If he is elected in an election in 2009, as is expected if the constitution passes, he would be able to remain in office until 2014 not 2019.

The issue of re-election in Latin America is a treacherous one. Many times re-election has been tantamount to lifetime appointment since Latin American electorates often seem to be so malleable to corruption, intimidation, patronage, and graft. However, allowing a second re-election seems to work fairly well in other countries, such as, for instance, the United States.

As has been the case in Venezuela, it is hard to oust a president who is democratically elected, but after elected, acts in many ways like a dictator and uses all types of methods – legal or not legal- to assure his reelection. Or, the administration, after solidifying power could urge another constitutional amendment to allow for indefinite reelection.

Confession of weakness

The objection to the re-election provision is also in large part a confession of weakness on the part of the opposition to President Morales. Here we are, almost three years into the Morales Era, and the opposition is nowhere close to being united and having leaders who could represent an alternative to Morales. The opposition party, PODEMOS, seems to be falling apart and due to the ill-advised recall referendum held in August, the opposition lost two of its five prefects. There is no apparent leader to act as a counter balance to Morales. The opposition thus far has done only a fair job of explaining what it is against, and as President Morales demonstrated in the recent recall referendum that if Bolivians are asked to vote si or no on him, a big majority will vote si.

“Autonomia,” the banner under which the opposition has gathered, remains a gossamer political precept whose precise meaning very few seem to be able to express in concrete terms. The most prevelant thought about what autonomia means seems to be something akin to the federalist system in Spain.

Autonomia is not "separatism"

President Morales, in a turn-around on some of his provocative oratory, this week took back what he had said about autonomia being a code word for “separatism,” but with even that misleading definition gone, the concept of autonomia seems even more diaphanous, and the opposition looks more and more like the Key Stone Cops. cops.

Passage of time is needed to see how many of these issues are going to be worked out (if they are). The major fact of the moment is the dramatic change in the mood of the country, particularly the city of Santa Cruz. In two weeks the prevailing sentiment has gone from expecting Armageddon any day now, probably in the form of a bloody shootout between Cruceños protecting their families and homes against the onslaught of an armed column of campesinos marching on the city to maim and kill, at the orders of the president.

Just 10 days ago the President was promising that the proposed Constitution would be passed, without even a comma changed, “come hell or high water.” The campesinos encamped in a “Woodstock Andina” in La Paz, it was feared, would blockade the Congress, preventing participation of non-MAS congresspersons, and effectively ending yje concept of representative democracy in the country.

Peace in our time?

Now the mood is much more sanguine. Friends who only weeks ago were talking about the inevitability of civil war, have reinstated previously canceled vacation plans. People we know were sitting around on back porches on a sunny afternoon yesterday explaining to one another how they always knew this was going to happen. (The most popular explanation for the sudden rapprochement: President Morales feels he needs a period of calm to insure his orderly re-election.)

The modified (and mollifying) Constitution is not the only sign that peace may be at hand (at least for a while). The government this week canceled bans on the export of soy and corn, which had been filling silos in eastern Bolivia to the bursting point. The agriculturalists are unhappy to have missed the high prices for their products that were in place until the current international financial crisis broke, but pleased to be back in business. (The government had claimed the export bans were in effect to reduce food prices, but it was widely believed that the bans were mainly an effort to punish the agricultural interests in the eastern plains, particularly Santa Cruz – the autonomistas.)

The long dormant Supreme Court has started making noises about giving jailed Pando prefect Leopoldo Fernandez a trial, and one that would take place in pro-autonomia Sucre, the constitutional capital of Bolivia where the Supreme Court is located, rather than in MAS-controlled La Paz. where Fernandez is being held.

Gas at last?

The government also claims it is at long last taking steps to end the shortages of diesel, gasoline, propane and other petroleum products facing Bolivians daily, but there are no apparent signs of relief yet. Some had thought that the shortages, occurring most often in autonomista areas, were a type of castigation but it appears, however, to be more ineptitude than planned punishment

The national pipeline company, formerly known as Transredes, appears to have been placed firmly in the hands of hacks and boodlers in its most recent wholesale change of personnel, where the Board of Directors decided that they wanted to become management and appointed themselves to the executive positions of President, Vice-president, etc. while many of them still remain on the Board.

The newest government appointee to the embattled national oil company board is an indigenous activist who cheerfully admits he doesn’t know nothin’ about pumpin´ no gas. He explains that he’s there to deal with the “social” rather than the “technical” aspects of the oil and gas business, but this is at a time when the oil company, falling behind on all fronts, is in desperate need of people who know at least whether or not pipelines should gurgle.

In short, the situation while more hopeful overall, remains confused and conflicted.

A friend reminds us that, as he has always said, the time horizon in Bolivia is never more than six months. But for now the next six months are looking pretty good.(if one discounts the dark cloud on the horizon presaging a global recession).

This weblog was created to provide a fuller and more accurate picture of the current situation in Bolivia. Our principal effort to try to pull things together and place them in proper perspective is the penultimate post below, titled "Main Story."

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

What a thorough analysis, along with relatively good news. This blog is a great help to those of us with a strong interest in Bolivia from afar. Thanks, David and Kelly.

Do you think the new constitution could have been influenced by the rapid reduction in energy prices over the last 6 to 8 weeks? With people like Chavez seeing their oil money drop in half, he is certainly much more quieter. Could the realization that free was coming to an end have pushed them into making the positive change?

I love this Blog. This is my first time reading any post here; nice insight.

Post a Comment