another easy victory

As polls had predicted, voters in Tarija approved new laws making the department (state) autonomous of the central government, which is currrently headed by President Evo Morales, a socialist and ally of Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.

According to preliminary official counts, the autonomy measures passed with about 81 percent of the vote. This was just about the average of previous referendums in the states of Santa Cruz, Beni, and Pando. However, the turnout in Tarija was somewhat higher, approaching 66 percent, making the victory even more impressive.

Morales party. the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS), never had any hope of defeating the measure, but had encouraged voters to abstain, and sought to disrupt the elections with blockades and boycotts. There were scattered incidents in which MAS adherents attacked polling stations and burning ballot boxes, but generally the voting was peaceful.

A commehtator in El Deber, the major Bolivian daily, contrasted the vote on the referendums, which took place openly in public squares, union halls, and other such places, with the proceedings of the constitutional assembly convened by President Morales, which had concluded its deliberations under guard in a military facility with only MAS adherents allowed to participate.

The vote in Tarija brings to four the number of provinces (out of nine) that have voted for autonomy. The prefect (governor) of a fifth department, Cochabamba, announced yesterday (June 22) that voters there will vote on autonomy in September.

Morales' government, and party, will be put to a test in another province, Chuquisaca, next Sunday when there will be an election for prefect pitting a campesina woman and former MAS advocate, against the MAS-backed candidate, together with a third candidate.

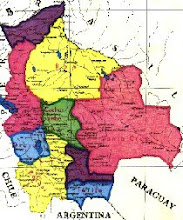

Tarija, Beni, Pando, and Santa Cruz are all located in Bolivia's eastern lowlands, and have called themselves the "media luna," or half moon, of Bolivia that opposes President Morales. These departments have never supported President Morales or his party, even in the election in which he won with more than 50 percent of the vote in 2005.

Cochabamba and Chuquisaca represent an intervening area between the lowlands and the highlands both politically and geographically, and are referred to as "the valleys." Both provinces voted for Morales in 2005, and a defection by either one would represent a significant diminution of his mandate.

President Morales apparently plans to get back on a winning track in a referendum in August in which the nation's voters will be asked whether they wish to retain or dismiss the president and the prefects of the nine departments.

This measure was approved, apparently in an aberrant moment, by the president's principal opponents, the Podemos Party, headed by former president Jorge "Tuto" Quiroga.

However, the recall referendum never had the full support, or even partial support, of the autonomia movement's leaders, who doubt that President Morales can be defeated in a straight up-or-down vote of the entire nation, and would would rather be about the task of building their autonomous regimes. At present there is talk that the autonomous regions may not even conduct the recall referendum.

Whose oil is it, anyway?

The referendum in Tarija brings into sharp focus the question of what "autonomia" really means.

Tarija goes to the polls Sunday to vote up-or-down its own version of “autonomia,” and much will be made of the fact that about 85 percent of Bolivia’s petroleum reserves are in that department (state) located along the nation’s southern border with Argentina.

The question then naturally arises as to what, exactly, could be the effect of a “yes” vote on autonomy there for Bolivia’s petroleum industry.

There is no simple answer. The apostles of autonomy say they have no plan to take control of the gas and oil fields and bypass the national government of leftist President Evo Morales in the marketing of the product. That would be the equivalent in Bolivia of pushing the nuclear button, and would trigger a civil war.

The autonomistas do talk about getting more control of the natural resources in the provinces that have voted themselves into this status, not total control. However, since recent decrees by President Morales have eliminated any claim that the regional governments have over oil and gas resources under previous law, it might be more precise to say that the autonomous provinces will be seeking to get back some control over these natural resources.

Indeed, Morales has clearly selected the issue of the proceeds from oil and gas to be the principal battleground in his government’s effort to centralize political and economic control of the country.

So far three of the country’s nine provinces – Santa Cruz, Beni and Pando – have voted for autonomy. Tarija would be the fourth if, as expected, it votes for autonomy Sunday, and that would just about complete a half moon-shaped segment of the country consisting mostly of the lowland plains region in the eastern half of the country. (A little finger of a fifth department, Chuquisaca, separates Tarija from Santa Cruz. Chuquisaca has not yet scheduled a vote on autonomia, and may not do so, though much of the province is at odds with the president, who was prevented from attending a civic holiday there recently.)

Not enough gas

At this same moment, Bolivia is facing a crisis in terms of not being able to produce enough gas to comply with contracts it has with Brazil and Argentina, along with internal demand. Natural gas in canisters (propane) for use in kitchens and for home heating is in short supply, with long lines forming to get it. Monday the government announced that military policemen will start riding on the trucks that deliver propane to keep order.

_________

SHORT SUPPLY --

Bolivia is not producing enough propane to meet internal demand.

There are reports that the government is actually planning to import propane, which would be expensive -- and embarrassing. “It would be like a banana-producing country having to import banana pureé,” says Carlos Delius, director of Kaiser, a petroleum services company, and a widely acknowledged expert on Bolivia’s petroleum situation.

Delius and other experts expect that autonomy will produce a subtle and complicated change in the negotiating relationship between the national government and the autonomous provinces that will enable the provinces to rise above their current position of being, basically, beggars.

They aren’t sure what the linkages will be in this process, which remains somewhat mysterious, but they note that the governors (prefects) have been declining the president´s invitations to negotiate until they have in place their autonomous mechanisms, which include a legislature.

The past is prologue

To understand what may happen in the future it is necessary to first know what has happened in the past. The discovery and development of major gas reserves in Bolivia is a relatively recent event, having occurred basically during the 1990s. And in the global scheme of things Bolivia’s hydrocarbon resources are relatively small.

It is customary to say that Bolivia’s gas reserves are exceeded only by those of Venezuela in South America, but putting things this way tends to give an exaggerated impression of Bolivia’s assets. South America, in truth, doesn’t have much in the way of proven petroleum reserves.

In terms of gas production, Bolivia ranks 34th in the world, flanked by Bangladesh and Burma. Its gas reserves total about one-half of one percent of the world’s. It also has some oil reserves, but these are negligible on a global scale, not quite covering its internal needs.

To get an idea of the difference in scale between Bolivia and Venezuela, a New York Times Magazine story last year said that Venezuela needed about 190 oil drilling rigs to maintain its current levels of production, and had only 70 available. A recent article in El Deber, Bolivia’s major daily newspaper, said that Bolivia needed 14 rigs to maintain its current production, and had only three.

Gas fuels Bolivia's government

However, while Bolivia’s reserves and earnings from petroleum products might seem small when considered on a global scale, they are of immense importance to this relatively small and very poor country. It’s estimated that the government currently gets about $2 billion a year from royalties and taxes on the oil business, which accounts for about 80 percent of its income, much higher than the 50 percent Venezuela’s government gets from its oil and gas industry.

But Bolivia has gone from feast to famine in terms of being able to exploit its gas reserves. Only five years ago, in 2003, its production capability seemed infinite, and the discussion was all about building a pipeline to the Pacific coast where the gas would be liquefied (converted into LNG), pumped onto tankers, and sent off to, among other places, California, which was then desperately short of energy.

The only argument seemed to be whether the LNG plant should be in Chile or Peru. The Chilean ports were closer, but Chile has been Bolivia’s ancestral enemy ever since it snatched away Bolivia’s seacoast during a very conflict in 1871.

Investment drops in 2003

But in 2003 international investors sharply curtailed their activities in Bolivia. In 2002 over $600 million had been invested in Bolivia by outsiders. That amount dropped by about half to around $ 300 million in 2003, and has trailed off from there to about $200 million. The last year in which over $1 billion dollars was invested in Bolivia's hydrocarbon industry was 1999.

There were several reasons for the drop in 2003. One was that the pipeline to Brazil had been completed, and there was no new market in sight because of the the seemingly hopeless stalemate that was developing over the Pacific LNG project.

Another was a general increase in the political instability of the country, fomented in large part by Morales, who was then a leader of the opposition and wreaking havoc by deploying his campesino followers in road blockades and other actions that paralyzed the country. However, it might be noted that the oil industry has had few qualms about sinking money into other politically troubled regions. Yemen and Nigeria serve as cases in point.

Delius, the expert on Bolivia’s gas situation, thinks that another, and possibly more crucial factor was the contract that Bolivia entered into to provide gas to Argentina. That contract, he says, did not have the same safeguards guaranteeing payment as Bolivia’s more carefully drawn contract with Brazil, and Argentina is widely regarded as one of the most fiscally untrustworthy countries in the world. It has often, and recently, welshed on its debts.

Is this deal sustainable?

Moreover, its state gas company was selling gas to Argentinians at a price way below what it was paying Bolivia, a seemingly unsustainable policy that has only worsened with time.

Currently Argentina is selling a million BTUs of gas to its citizens at a subsidized price of $1.40, although that amount of gas costs Argentina $7. In fact, to make up for the large shortfall in the deliveries of gas from Bolivia (which the Argentine government is keeping quiet about), Argentina is importing LNG by ship that is costing $15 for the same amount.

Morales’ decision, taken in 2006, to “nationalize” Bolivia’s hydrocarbon industry did nothing to reassure the international investment community. The companies currently are spending just enough to keep their investments from deteriorating. “They are hostages to their sunk costs,” says Delius.

(As is discussed elsewhere on this weblog, Morales “nationalization” was more a “forced renegotiation” that did dramatically increase the amount the government received -- from $320 million annually to $2 billion currently. However, thanks to rising energy prices the companies, all of which stayed in Bolivia until very recently, were also able to increase their return on their investments, according to Delius. In May, Morales did confiscate the pipeline company, Transredes, an action that will be thrashed out in international arbitration. The government also took over a controlling interest in three other petroleum-related companies. (See article below in "Reporters' Notebook")

The result of all this has been that Bolivia has been unable to increase production fast enough to keep pace with the increases required by its contracts with Brazil and Argentina, and rising internal demand. Delius estimates that it fall short of the total needed by about ten percent this year, and that, if nothing is done, the gap will widen in future years.

This is a fairly dire prediction because Bolivia’s contract with Brazil requires Bolivia to pay fines if it doesn’t deliver the amount of gas promised in the contract. Civil unrest within the country resulting from gas shortages is another threat to be reckoned with.

Bolivia’s increasing unreliability as a supplier was one factor driving Brazil’s recently successful effort to discover gas reserves on its own territory and become independent of reliance on Bolivia. It has found huge gas deposits under the sea off the coast of Santos, a principal port, and might actually become a gas exporter itself in a decade, according to Delius. “It could be another Gulf of Mexico,” he says.

No shortage of demand

Still, there will be plenty of demand for Bolivian gas in the region, which will face an escalating energy shortage for the foreseeable future. “What people have to realize,” says Delius, “is that Bolivia’s gas is not the same as a surface diamond mine, where you can get more diamonds by just kicking the dirt away.”

The gas is thousands of feet underground, and development the five to seven new megafields that Bolivia will need to meet its needs over the next 40 years will require billions of dollars – at least a billion a year over the next seven years.

Delius, for one, thinks it can be done, but the government’s current strategy of screaming at the international oil companies to invest more money will not do the trick. The companies, he notes dryly, can hardly be held to account for failing to fulfill production plans for 2008 that the government, as a result of bureaucratic inertia, has not yet approved.

What’s needed, he says, is a change in stance by the government that will guarantee the operating companies' income stream. The oil companies and the government don’t have to love each other. They just have to trust each other.

If that happened the companies could overcome the short-term shortfall by uncapping wells that have been capped for various reasons. Bolivia’s need for drilling rigs to solve the longer-term problem is sufficiently modest that it could be overcome despite the current world-wide shortage of such rigs.

“If one of the big companies working here like Total (French) or Repsol (Spanish) went to a drilling company in Houston, and showed that they had a guaranteed income, that company in Texas would build them five rigs. It would go to China for the parts, if necessary.” The ability of the oil industry to overcome obstacles when there is a large profit to be made cannot be over-estimated. he says.

Then, he adds, it would also help to renegotiate the contract with Argentina to make it a little more ironclad. Such a renegotiation is already being spoken of, but mainly for the purpose of lowering the quantity of gas Bolivia is obligated to ship by pipeline to Argentina. Delius fears the renegotiation could also lower the price Argentina is paying.

Militant anti-globalists

The big reason that Bolivia is unlikely to take this route out of its current impasse is that the Morales government is split in its attitude toward the country’s oil and gas industry. About half the people in it are devout, doctrinaire anti-globalists who want the country to secede from the global economy.

They see the petroleum industry -- and particularly the newly strengthened national petroleum company -- as a source of patronage jobs and short term gains. In short, they are ready to eat the goose that lays the golden eggs.

“I have explained the situation to them as forcefully as I can,” says Delius carefully, “but some of them just . . . couldn’t . . . care . . . less.”

On the other side is a contingent, probably including the president (at least at times), that wants to keep the goose laying, and sees continuing gas revenues as necessary for the part’s political and economic aims no matter how repugnant they find multinational oil executives and their ilk. At the present moment the intramural battle within the government seems to be a stand-off.

If the departments are able to gain a better bargaining position with the central government, possibly by taking or threatening actions that are unrelated to petroleum, that might strengthen the hand of those in the government who want to keep the gas business at least at current levels. On the other hand, it could also further radicalize the anti-globalists, making them even more rabid.

Certainly Morales has demonstrated an eagerness to get control of the gas revenues. His decree earlier this year annulled a previous law that had guaranteed the departments and municipalities a fixed percentage of the oil and gas revenues, eleven percent in the cases of the departmental governments in Tarija and Santa Cruz.

This money was used for development projects, particularly highway and bridge building, which are badly needed. At present there is no paved road from Bolivia’s eastern border with Brazil to its western border with Peru, and the part that´s paved is badly paved. Much of the national highway system is of lower quality than the average American suburban driveway.

Morales has said the money was needed to continue funding the country's rudimentary social security program, as well as for his party’s recently unveiled Soviet-style five-year plan. However, the president’s critics say he is using his control of the funds in Machiavellian fashion to reward political loyalists, and punish political enemies.

The departments, of course, want the old system of revenue-sharing reinstated, and perhaps even expanded. That will be the basis for the arm-wrestling match between the government and the autonomous departments that will begin soon.

When and where it will end no one can say.

No comments:

Post a Comment