block presidential visit

Rock-throwing youths took control of the streets of Sucre Saturday, forcing soldiers to retreat from the center of the city, and preventing a carefully planned foray into the city by President Evo Morales.

The out-of-control youths, took prisoner a group of about 30 campesinos, marched them through the city, stripped off their shirts, stole their money and watches, and ultimately forced them to kneel in the central plaza and beg pardon for coming into the city to takeover the streets. It was an ugly scene that may lead to violent revenge.

_____

ON THEIR KNEES -- Youths forced these MAS adherents to beg pardon for coming to the city. Photo from El Deber.

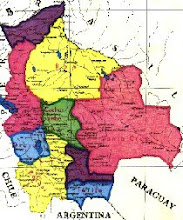

The occasion for the presidential visit was the annual celebration in Sucre of the "first cry of freedom," saluting the fact that Sucre was the first city in Latin American where a movement for independence from Spain took form.

Several other cities in what became Bolivia soon followed suit. However, the independence movement in this area was ultimately suppressed, leading to the historical irony that although the first cries of freedom were heard here, Bolivia would be the last part of the Spanish Empire to actually become independent.

Sucre has been a hotbed of anti-Morales sentiment ever since mobs forced the constitutional assembly to flee the city last year, after the conclave had been split on the question of whether the central government should be completely moved back to Sucre from La Paz. (The executive and legislative branches moved from Sucre to La Paz after a civil war a century ago. Sucre is still the home of the supreme court.)

Carefully arranged visit

The presidential visit had been designed to be a highly controlled affair inside a stadium which was to be packed with pro-Morales supporters, and ringed by soldiers. However, the mobs of young people took control of the streets around the stadium early in the day and ultimately forced the soldiers to retreat, cowering under a hail of rocks being thrown at them.

By Sunday the violence in the city had subsided, but campesinos in the surrounding countryside were blocking all roads into the city, and threatening to cut the city's main water supply, as well as its gas supply. Civic leaders were busily apologizing, though in some cases rather weakly, for the violence. A spokesman for Morales castigated the civic authorities for failing to keep order. The Catholic Church was offering to mediate, leading the newspaper El Deber to headline its Monday story, "Sucre Between the Cross and the Sword."

A civic ceremony commemorating the "first cry of freedom" went forward Sunday, though without the participation of the Army troops who were scheduled to be in the procession. The only police present were those assigned to protect the judicial buildings in the city.

THINGS HAD BEEN COMPARATIVELY CALM in the country in recent weeks, during the run-up to the departmental autonomia referendum in Beni this Sunday. The referendum is regarded as sure to pass, with the main question being whether Benianos will exceed the 85 percent vote in favor of autonomia recorded in Santa Cruz May 4. In 2006 Beni did approve the measure that paved the way for the votes on autonomia by a wider margin than it got in Santa Cruz.

Meanwhile the autonomic process had been chugging along steadily in Santa Cruz, where the prefect, Ruben Costas, had been proclaimed governor, and an advisory council converted into a regional assembly. President Morales and his ministers had been content with grumbling that it was all illegal.

The looming confrontation over the central government's attempt to halt exports of vegetable oil, an important industry in Santa Cruz, had been defused with agreements allowing the major companies to export for a limited period of time, with various extra reporting requirements laid on them in what seemed like an effort to avoid the appearance of complete surrender.

Fiddling with salaries

Both the fledging regional government of Santa Cruz and the central government are working on various ways to monkey with salaries that impede the workings of the free market, but illustrate the differing directions in which they are headed.

The first major law to be passed by the departmental assembly is apparently going to be a minimum wage law, requiring that every salary earner in the department of Santa Cruz to be paid at least 1,000 Bolivianos (about $136 US) per month.

No one is voicing the usual objections to minimum wage laws, namely that they result in the laying off of marginal workers and hasten the replacement of human labor with machines. And in Bolivia the cost of labor is so low that those objections may not apply.

The major resistance is coming from restaurateurs and service businesses who say they simply can't afford to pay employees that much.

The real test will probably be enforcement. Some foreign businessmen have suggested that a better first step would be to require that companies actually pay what they have pledged to pay employees, and pay it on time. Foreign companies often find they can cream the local talent pool simply by meeting their payrolls.

Lowering oil company salaries

For its part, the central government is seeking to lower some salaries. (To be fair it did require pay raises earlier, though not to the level contemplated by the Santa Cruz leaders, who clearly want people to feel a tangible benefit from the somewhat abstract concept of autonomia.)

The government recently acquired a majority share in four of the 10 oil companies operating in Bolivia, and promptly announced that henceforth no employee of the companies could earn more than $12,000 a year. About 100 employees in the four companies were reportedly earning salaries above that level.

But this is likely to produce problems. The companies presumably need the services of a few petroleum engineers, and the American Society of Petroleum Engineers recently reported that the average petroleum engineer is earning $124,000 a year. (You can get one without experience, though, for around $70,000.)

Moreover, petroleum engineers are becoming increasingly hard to find. The number being graduated has been in decline, and half of those on the job today are expected to retire in the next ten years, a big chunk of them in the next two years. Petroleum engineering supposedly offers better earning potential at present than law or medicine.

The rate of increase in production in Bolivia's oil and gas fields has slowed dramatically in the last two years, and the country is currently having difficulties meeting its contractual requirements for gas shipments to Brazil and Argentina. There are also chronic shortages of diesel fuel.

It all reminds one of Winston Churchill's observation that "capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings, while socialism is the equal sharing of misery."

1 comment:

Keep up the good work.

Post a Comment